|

|

Gladiators: An Introduction

by: Gaia Aelia Cleopatra

Gladiators come into the mind of people when they think of something typical for the Ancient Roman culture, mainly also in connection with amphitheaters of which the Amphitheatrum Flavium (the so called Colosseum) is the best known. But what do we really know about this typical Roman institution?

Origin of the Gladiatorial Games

The first recorded gladiatorial fight in Rome took place at the Forum Boarium in the year 264 BCE at the funeral of Decimus Iunius Brutus Pera and was organized by his sons. Three pairs of gladiators fought against each other at his funeral pyre. We can assume that there were gladiatorial fights in Rome before but they were not recorded. We know that the tradition of gladiatorial combats did not evolve in Rome but in other places in Italia.

Sacrificial killings at a funeral pyre existed in other cultures as well, e.g. in Greece. The Iliad reports that Achilles cut the throats of twelve noble Trojan sons at the funeral pyre of his dear friend Patroklos. This scene is depicted even on the walls of Etruscan tombs. They show many other kinds of duels as well, but all in a mythological context. We know of the Mycenaean culture that they had the rite of either the human sacrifice, armed duel or sportive agon (competition). So the tradition of an armed duel at a funeral could have been brought from Greece to Italia.

Remarkable is the fresco of a man wearing the mask of the Etruscan demon Phersu who sets a dog on a man blindfolded by a hood. This is not a gladiatorial bout but some historians see in it a predecessor to venationes (beast hunts) or damnatio ad bestias (conviction to beasts). These two became part of the munera only in the late Republic and had no connections to gladiator fights before.

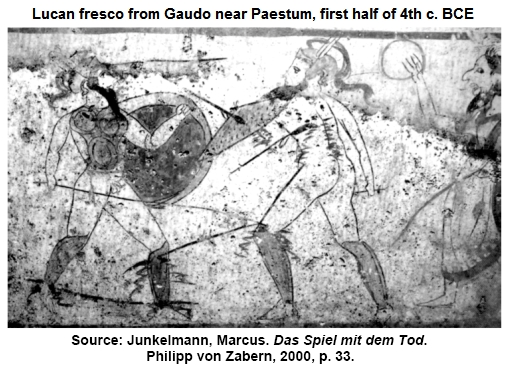

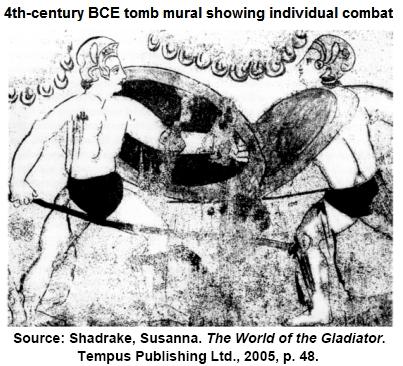

In Campania (South Italy) we find tomb paintings of Osco-Samnite origin which show two combatants fighting each other nearly equally equipped. Tomb 7 of the necropolis Gaudo near Paestum shows fighters wearing Attic helmets of South-Italian type, greaves, large round shields and the left figure even wears a pectorale. They attack each other with spears and the right one is already wounded. Another picture, also from Paestum, shows two helmeted fighters, similarly equipped as described before, but now with other protective armor than the shield and helmet. They are both wounded.   Besides these paintings showing something which might be early types of gladiators there is another strong evidence that Campania might be the origin of the gladiatura. The first amphitheaters were built there and the most renowned ludi (gladiator schools) were established there long before the imperial Ludus Magnus was founded in Rome. Further the historians Livius, Strabo and Silius Italicus state that at Campanian banquets gladiators fought to entertain the evening party.

As mentioned in the beginning the first gladiators in Rome fought at funerals next to the pyre which was called bustum. Therefore these very first types of gladiators were referred to as bustuarii. It was believed that the ritually shed blood reconciled the dead with the living. The first gladiator games were therefore privately funded. Because they became popular with the people, rich people - e.g. running for public office - used them to boost their popularity. So it happened that the munus – which means duty or obligation – was not held in near time to the funeral but could happen even a couple of years later when it seemed most benefiting. Hence the Senate enacted the law that it was not allowed to hold munera less than two years before running for public office.

The first gladiators were prisoners of war and most probably fought with the weapons typical of their origin. The names of early gladiator types reflect this, since they were called Samnite or Gaul. Unfortunatly it is not known what their exact armatura was because it might not have been totally identical to that of a Samnite or Gaulish warrior. Later on it was not any longer a Samnite who fought as a Samnite, e.g. Spartacus who originated from Thracia fought as a murmillo but not as a thraex. Their armatura was adjusted to the needs of the arena.

Even though politicians used gladiatorial games to boost their popularity, they were always held in connection with a deceased relative and privately funded. In the Republican era the aediles were responsible for financing gladiatorial games during their term of office, so it was a costly position; but you had to be aedilis before you could run for office as praetor. The first publicly funded gladiator shows were the ones hosted by the Senate after the assassination of C. Iulius Caesar in 44 BCE.

In the Imperial Age the munera were hosted by the Emperors, but only on special occasions; they never became part of the regular festive calendar like the ludi which included chariot races (ludi circenses) and theater shows (ludi scaenici) which all had a religious background.

In the provinces the magistrates could hold also munera; at some municipia it was obligatory for the newly elected magistrate to host games of some type, e.g. at Urso, a colony in Baetica (modern-day Portugal) the aedilis was required to host either a munus or ludi scaenici during his magistracy, as it was stated in the lex Ursonensis.

Besides these paintings showing something which might be early types of gladiators there is another strong evidence that Campania might be the origin of the gladiatura. The first amphitheaters were built there and the most renowned ludi (gladiator schools) were established there long before the imperial Ludus Magnus was founded in Rome. Further the historians Livius, Strabo and Silius Italicus state that at Campanian banquets gladiators fought to entertain the evening party.

As mentioned in the beginning the first gladiators in Rome fought at funerals next to the pyre which was called bustum. Therefore these very first types of gladiators were referred to as bustuarii. It was believed that the ritually shed blood reconciled the dead with the living. The first gladiator games were therefore privately funded. Because they became popular with the people, rich people - e.g. running for public office - used them to boost their popularity. So it happened that the munus – which means duty or obligation – was not held in near time to the funeral but could happen even a couple of years later when it seemed most benefiting. Hence the Senate enacted the law that it was not allowed to hold munera less than two years before running for public office.

The first gladiators were prisoners of war and most probably fought with the weapons typical of their origin. The names of early gladiator types reflect this, since they were called Samnite or Gaul. Unfortunatly it is not known what their exact armatura was because it might not have been totally identical to that of a Samnite or Gaulish warrior. Later on it was not any longer a Samnite who fought as a Samnite, e.g. Spartacus who originated from Thracia fought as a murmillo but not as a thraex. Their armatura was adjusted to the needs of the arena.

Even though politicians used gladiatorial games to boost their popularity, they were always held in connection with a deceased relative and privately funded. In the Republican era the aediles were responsible for financing gladiatorial games during their term of office, so it was a costly position; but you had to be aedilis before you could run for office as praetor. The first publicly funded gladiator shows were the ones hosted by the Senate after the assassination of C. Iulius Caesar in 44 BCE.

In the Imperial Age the munera were hosted by the Emperors, but only on special occasions; they never became part of the regular festive calendar like the ludi which included chariot races (ludi circenses) and theater shows (ludi scaenici) which all had a religious background.

In the provinces the magistrates could hold also munera; at some municipia it was obligatory for the newly elected magistrate to host games of some type, e.g. at Urso, a colony in Baetica (modern-day Portugal) the aedilis was required to host either a munus or ludi scaenici during his magistracy, as it was stated in the lex Ursonensis.

Types of Gladiators in the Imperial Age

The first Emperor Augustus reformed the gladiatura. Some old types such as samnis and gallus disappeared while the thraex, provocator and murmillo still existed. As mentioned before gladiators could have been prisoners of war, but also slaves sold by their master to a ludus, or even volunteers (called auctorati). If the auctorati were Roman citizens they gave up their rights as a citizen such as running for office or being able to join the legions, and they were deleted from the lists of the property owning citizenry. All gladiators had to swear unto their lanista the sacramentum gladiatorium (gladiatorial vow) “uri, vinciri, verberari, ferroque necar patior” (to be burned, to be enchained, to be beaten and killed by the iron). After three years the gladiator could gain his freedom or he bought it even before that time with his prize money.

Each gladiator specialized in one class of fighting although we know from epitaphs that there had been some who fought as both murmillo and secutor (these two categories are very similar), or as both murmillo and provocator. The scholars assume that the gladiator began his career as one type and then changed to the other.

Let us have a look at some Imperial types of gladiators:

-

Eques (“Rider”)

- The equites opened the gladiatorial fights in the afternoon. They rode into the arena on white horses and fought from horseback with lances. Then they dismounted and continued the fight on foot using their gladii. On most depictions they are shown in this later phase of combat.

Besides the aforementioned offensive weapons – hasta and gladius – they wore a helmet with a wide brim and visor, and a round shield. They were the only type of gladiators who wore a tunic instead of the subligaculum (loincloth).

- Murmillo (also myrmillo or mirmillo)

- As mentioned before the murmillo is a very old type and existed already in the 1st century BCE, but his origins remain unclear.

The murmillo was equipped with a gladius and a scutum. He wore a manica to protect his sword arm and an ocrea (greave) on his left leg. His helmet with a visor had a high angular crest which was decorated with colorful feathers. His standard opponent was the...

- Thraex (also thrax, threx, the “Thracian”)

- The armatura of the thraex still reflected his origin from Thracia. He was equipped with the sica (sword with a curving blade) and a parmula (small rectangular curved shield, in contrast to the large scutum). His visored helmet had a crest which ended always in a griffin head. Like the murmillo he also had a manica to protect his sword arm. He also had padded leg protection over which he wore a pair of high greaves which ended above his upper thigh.

- Hoplomachus

- An alternative to the pairing murmillo – thraex could have been the pairing murmillo – hoplomachus. Exceptionally the hoplomachus could fight also against the thraex. The hoplomachus greatly resembled the thraex, except that he had a hasta instead of the sica and a parma (a round shield similar to the Greek hoplite shield). For close combat he had a pugio or gladius.

- Retiarius

- This is the most uncommon type of gladiator and documented only from the reign of Caligula on (37-41 CE on). His unusual armatura consisted of a rete (net), a trident (fuscina or tridens), and a pugio or gladius. He had neither a shield nor a helmet. His only protection was a manica with a galerus (shoulder guard) on the left arm. At first he tried to throw the net over his opponent to get him entangled in it. If it was thrown without success he tried to fight his adversary with the trident. For close combat he had to use the pugio or gladius. His standard opponent was the...

- Secutor (the “Pursuer”)

- He was a kind of murmillo specialized in fighting the retiarius, the only difference was the helmet. He wore an egg-shaped helmet with a smooth featureless crest so the net of the retiarius could not get tangled. The helmet had not a visor with a grille but with eyeholes only to prevent the prongs of the trident getting through the visor.

A special form was the combat of a retiarius standing on a kind of a bridge (pons) fighting against two secutores who tried to climb the bridge via ramps on each end. Additionally to trident and sword/dagger, he had stones he could throw at his adversaries.

- Scissor (the “Slasher”)

- This was a rare type of gladiator who could also fight the retiarius. He wore the same helmet as the secutor and also carried a gladius in his right hand. His sword arm was protected by a manica. He did not carry a scutum but his left arm was tucked into a tube which ended in a blade of the shape of a mincing knife. With this weapon he could slash the net of the retiarius to pieces and parry his trident. Also he could disembowel his rival. Because he could not protect his body with a shield he wore a coat of mail (lorica hamata) or a scale armor (lorica squamata) which reached down to his knee.

It is not clear if he fought the retiarius only instead of a second secutor for the fight at the pons or if he faced the retiarius also as single opponent.

- Provocator (the “Challenger”)

- This gladiatorial category is known since the late Republic and fought – like the eques – always against his own type. In the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE he wore a helmet which resembled a legionary helmet. In 2nd and 3rd centuries CE he had a helmet without a crest and a deep neck-guard with a visor. He had a scutum, a lunar- or bib-shaped pectorale (breast plate) and a gladius. Further protection were an ocrea on the left leg and a manica on the right arm.

- Gladiatrix

- There were women who fought in the arena, even though it was not that common. It is not known in which categories they fought except on this famous relief from Halikarnassos (today’s Bodrum in Turkey) which shows them fighting as provocatrices. But it is possible that women could have fought in all types.

- Essedarius

- This was another gladiator type fighting only against his own. The name derives from the name of the Celtic chariot. Most probably the essedarii started their fight from the chariot and then dismounted to continue the combat on foot.

The essedarius was equipped with a manica on the sword arm, with a gladius, and with gaiters or short bandages on both legs. His helmet looked similar to a legionary helmet in the 1st century BCE and then like a secutor helmet.

- Dimachaerus

- This is a very rare type, mentioned only twice on inscriptions, who is supposed to have fought with two swords. About his further equipment nothing is known. Inscriptions from Pompeii tell that dimachaeri fought against hoplomachi.

- Sagittarius

- On a relief in Florence two armored and helmeted archers are shown who shoot at each other in an arena.

- Andabata

- Cicero mentioned this category but in the Imperial time there is no further proof of this type. It remains unclear if it is a category of its own or if it is just regular gladiator types fighting against each other blind-folded.

- Laquearius

- Isidore of Seville is the only one mentioning lasso fighters who catch fleeing people in an arena. The evidence is that they are more likely arena hands assisting the executions of noxii than being real gladiators.

- Paegniarius

- The paegniarii fought without lethal weapons but were equipped only with whips in the right hand and wooden boards on the left arm. They fought with both arms at the same time. It seems like that they appeared only at the prolusio (opening fights).

- Veles

- The velites are another type mentioned only by Isidor of Seville as well as on some inscriptions where the abbreviation VEL is found. The name is derived from the most lightly-equipped Roman soldiers from the time of the Punic Wars. Most likely their fighting style was similar to that of these soldiers.

- Crupellarius

- Tacitus mentioned the crupellarii as Gaulish fighters. A bronze statuette from France might show one of these fully armored fighters.

- Scaeva

- If a gladiator fought as a southpaw it was worth mentioning. Emperor Commodus, who liked to appear as a gladiator in the arena, fought as a secutor scaeva. When two southpaws fought against each other it was called a pugna scaevata (left-handed fight)

How Gladiators were seen by Roman Society

The Romans had an ambivalent feeling towards gladiators. In the arena they were admired in a way we admire sports stars of our time. Of all performances that of the arena was the most valuable, followed by chariot racers and then by the actors. One reason for this was that the gladiators showed virtus, the highest Roman moral quality. It consisted of the following:

- Fortitudo (strength)

- Disciplina (training)

- Constantia (steadiness)

- Patientia (endurance)

- Contemptus mortis (contempt of death)

- Amor laudis (love of glory)

- Cupido victoriae (desire to win)

It was recommended for soldiers to watch gladiatorial displays at the amphitheater to encourage them by looking at the gladiators who fought without fear, because they represented the moral qualities which were also required from a good soldier. Theater shows were regarded as the opposite because they were for pure entertainment only and had no educational purpose.

A reason for the popularity of the munera was that a gladiatorial bout was a demonstration of power to vanquish death. The victorious gladiator conquered death by showing that he was a better fighter than his opponent. And even the loser could overcome death if he had fought so well and bravely that the editor granted him the missio. Even if a gladiator had to die he died the death of a Roman citizen through the sword. By accepting the coup de grâce he died a quick and painless death and could show at his very end virtus. Some gladiators were so popular that their fans kept book about their fights by writing graffiti on the walls as were found in Pompeii.

Nonetheless in society gladiators were stigmatized as infamis, disgraced, and they ranked below chariot racers and even actors. Most gladiators were recruited from prisoners of war and slaves but even Roman citizens who decided to became gladiators voluntarily were considered infamis. This ment that they disappeared from the property-owning list, were no longer allowed to take a post in local government and could no longer be called up for military service. Practically speaking all gladiators were slaves and belonged to their lanista.

It was a rude word to call someone a “gladiator”; Cicero called his political rivals Marcus Antonius and Publius Clodius that way.

It was disgraceful for young men (and women) of the noble classes (senatorial and knightly families) to appear as gladiators in the arena. Many trained at a ludus but never fought publicly or only with wooden weapons. Basic gladiatorial training was given at the collegia iuvenum, which young boys and even young girls of high society attended. The worst was when they signed up as auctorati (volunteers) and became part of a familia gladiatoria and fought as real gladiators with sharp weapons at the munera. They had to swear the gladiatorial oath to the lanista as every other member of the familia. From now on there was no difference between the auctorati and the other gladiators, except that they could leave after three years if they survived that long, and that most probably they were allowed to leave the ludus to stay at home.

Why were young men (and women) attracted to become a gladiator when at first sight this had only disadvantages? One reason might have been to get away from military service because as a volunteer gladiator you signed up a contract of three years only while military service was between 20-25 years. And once you survived your first fights as a tiro (recruit) chances were not too bad that you made it until the end of the three years.

Gladiators were allowed to keep their prize money they won so they could make a fortune. This was very attractive to people hard-pressed for money.

And some people simply felt attracted to the fame they could earn in the arena.

| |